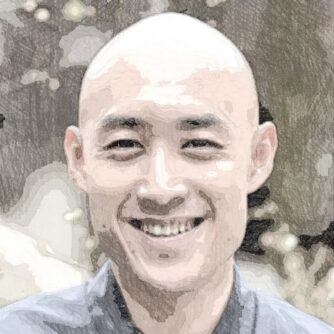

In the previous episodes, all of my guests have referred to the “younger generation.” So, it is only fair to give that generation a say. My guest, Tomo Kumahira is a bona fide millennial, turning 30 this year. However, he is not a typical Japanese millennial. He is an executive at a forestry company based in Kenya, and has been selected as one of the elite social entrepreneurs in East Africa. Let see where he comes from, and what makes Tomo tick.

https://www.linkedin.com/in/tomo-kumahira-b5b2277b/

Tomo was born and raised in Japan, and in his younger years, he describes himself as being “conservative,” and thought that perhaps he would work in foreign diplomacy or government policy.

But, as a university student in Tokyo, he attended a session featuring Drew Faust, then the president of Harvard University, the first woman in that position. This moment changed Tomo’s outlook on life.

She spoke about liberal arts education、how it was all about training yourself and life-long of learning. This was a very different perspective from what Tomo had experienced in Japanese education, which was all about preparing for work beyond graduation.

Tomo was not a typical college student in Japan where most of them were either studying or engaging in “bukatsu” (club activities). He quit the kendo (Japanese fencing) club after 3-4 month. Though he admired the sport, there was too much peer pressuring. This did not resonate with Tomo.

He questioned himself, “How can I contribute to society, without being completely being confined in comfort zone.”

When he was younger, his parents who had worked abroad suggested to Tomo to attend an international school, but the 5 year old didn’t want to. He was Japanese, living in Japan. Why should he attend an international school. His parents respected his opinion.

So, when Tomo proposed that he wanted to transfer from Keio University to Brown University in the US, they were very supportive. His close friends and teachers thought that it was a great idea that Tomo was taking a leap beyond the comfort zone.

But others were critical. “If you go out of circle you can never come back.” “How can you betray our university.” Yet, interestingly, these critics became Tomo’s supporters years later, sharing his experiences on social media.

Tomo was shocked when he enrolled in Brown. At the welcoming ceremonies, he was told by the keynote speaker that, “We are all started here in this learning ground, and we are still learners just like you, maybe a just a little bit longer, but we are excited to learn from you.” No teacher in Japan had ever asked to learn from students.

But expectations were very high at Brown. In Japan, a university student either studied or exceled in sports/club activities. At Brown, earning a high GPA was expected, as well as exceling in extracurricular activities, and also to make friends. A sign said “Sleep, Study, Friend, pick two of three.” Tomo managed to shift around all three.

In a required history class on American imperialism, he remembers the experience of discussing World War II with American, British, German, Italy, Chinese as well as Asian students. There was some awkwardness about history, but Tomo tried to overcome this by listening. He found that he can express condolences without being apologetic.

Tomo spent a summer internship program at Ashoka with their impact investment team. As a student, however, he felt that in order to add value, he lacked business experience. He thought that, after graduation, it would be better to find opportunity to learn about business and investment.

He found that job at Mitsubishi Corporation. Their asset management business had three decades of experience in building new funds. Even though most hires into Japanese companies cannot choose what division they will be assigned to, Tomo managed to persuade the company to send him to the “right team,” where he can learn about investment and pursue his passion for impact investing.

His rationale was that if he joined an American company, the job description would tend to be a specialist, which would confine him to a narrow scope. But, his mandate at Mitsubishi Corporation was investing everything outside of Japan, and this of course would allow him to experience a wide range of activities from Africa to North America, and from Growth Venture to Real Assets.

But, it must have been difficult for Tomo to come back to Japan after such a liberal experience living abroad in the US. However, Tomo told himself that his next phase in Japan would be an “anthropological exploration”, not his livelihood. This mental detachment made him see things as a “curious puzzle,” rather than a “shock.”

Tomo also raises a very interesting perspective. The 3.11 earthquake in Tohoku in 2011, raised conscious with the younger generation, that the Japanese system was no longer working. The generation born during Japan’s “lost decades” was told that Japan was a great country with diligent hard-working people, despite the many metrics that indicated otherwise.

However, with the 2011 earthquake, everyone saw the resilience of the people on the ground, but not so much with elites in the society. This left a question mark especially with the empowered younger generation in Japan. Politics and corporate mentality showed that they cannot respond appropriate to crisis. Tomo asks, as responsible members of society, how can we contribute to.

10 years later in 2021, Tomo is currently an Acumen Fellow for East Africa. Looking back, he feels that it was Mitsubishi Corporation that paved the road for his journey. The company was always looking for what is the right next asset class that has not yet been explored, and how can that have the meaningful contribution to society including impact investing. Tomo’s question led him to forestry and agriculture.

There are currently 1billion people in the world suffering from poverty, of which 60% are small scale farmers. Urban issues are more complex, but for agricultural development in rural areas were more straightforward. Access to seedlings and water, typical, and other capital intensive issues. However, Tomo found that investors wanted to invest more in such areas, it was difficult to find sound investment opportunities.

This was the “Aha” moment for Tomo. Investors needed to find investment opportunities with social impact, but in fact, most social enterprises were very passionate about what they were doing, they were not business oriented. The key was the social entrepreneur.

He searched the field like an investor, and that is how he found Komaza, founded by a Brown graduate. Komaza was just transforming itself from an NGO to a social enterprise just being able to raise Series A round, and now expand itself currently as a Series B social enterprise, looking to raise $30 million for investments across Africa.

He convinced the founder of Komaza to give him a shot as a fellow to support the CEO as a trial base. His pitch was “Hey, I am curious to see how I can add value.” He got the position and moved to a town of 50,000 people in Kenya, with just one supermarket.

Going from Keio University to Brown University, a prominent institution for higher learning was understandable. But, leaving the comforts of Mitsubishi Corporation to a forestry start-up in rural Kenya, obviously raised some attention.

His closest friends close congratulated him, and Tomo’s schedule for lunch and dinner was immediately filled up for 60-70 days. Others thought he was crazy. However, Tomo saw the potential with Komaza, a social enterprise partnering small holder farmer to plant trees for commercial purposes.

Tomo describes Komaza’s business model as the Airbnb for forestry. Instead of being asset intensive by buying the land to plant trees, the activity already existed. Therefore, Komaza just provides seedlings and fertilizer to build good tree portfolio that the farmers can eventually sell it to Komaza, which process wood for products with a higher price tag.

Komaza does not require land ownership for operation, but as a result, they account for 40 to 50% of new tree planting for Kenya every year. In the coming 3 week period, the plan is to plant 2 million seedlings by Komaza, worldwide. Their ambitions are to scale their business beyond Kenya.

Farmers are like investors or entrepreneurs. Under their severe environment, they do not concentrate in a single crop like maize, but they have planted trees to diversify risk and preserve capital for the long term.

Komaza portfolio currently consists of 25,000 farmers. They hire local youth in the community as a touch point and reminder of their presence. The local government also is consulted on local signings to make sure the farmers honor their commitment to Komaza in the long term.

It takes years for trees to grow. Therefore, the first 10 years of Komaza’s operations were based on donation. They started as an NGO, but became a company when they confirmed that the program was working, and therefore was able to start raising capital from the market. They are currently still burning cash, but are confident that their projection is headed in the right direction.

Tomo was chosen as one of the 23 Acumen Fellows for East Africa in 2021. Acumen, established in 2001 by Jacqueline Novogratz, is one of the most widely recognized pioneers in impact investment. A fellow must live and work in the chosen area, and have tangible impact either as an entrepreneur or organization builder to scale impact. The one year program is about leadership development, asking and answering lots of questions in a very tough environment.

When faced with tough problems, Tomo basically forgets his identity as Japanese. Other young Japanese leaders in similar situations are the same. They are so Japanese, yet, they never talk about it.

Tomo feels that for his generation, it is less about applying Japanese wisdom or technologies and searching for problems, but more about figuring out the biggest problems in society and how it can be solved. And, inevitably, the solutions can be found in Japan, because we are Japanese.

So for Tomo, the “Made With Japan” model is about being “part of” rather than being “belonging to.” He feels “Made With Japan” happens when his generation focuses on solving the problems, and there are lots of solutions that we can find from Japan. That is the moment that his generation can be proud of being Japanese, and to learn from great lessons from earlier generations. When Tomo turns 60 years old in about 30 years, he still wants to commit to solving problems, asking the big questions of how he can be useful. In that sense, it is likely to be the same questions he was asking when Tomo was a 20 year old college kid. He hopes to be open enough and curious enough to ask that question then. Good food for thought for us 60 year olds…. !