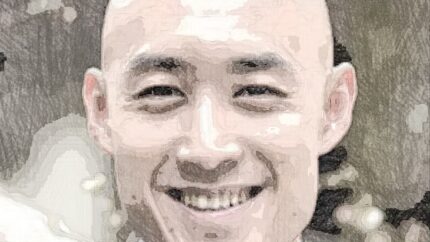

Shoukei Matsumoto is a contemporary Buddhist monk. Just like traditional art and contemporary art, a contemporary Buddhist monk alongside a traditional Buddhist monk should be acceptable. Typically, images of Buddhist monks are serving ceremonial rituals and supporting functions at their temple, but those activities are only a little part of Shoukei’s daily life. He spends most of his time creating a frontier for the role of contemporary Buddhist monks in the modern world.

https://www.linkedin.com/in/shoukeim/

Shoukei’s motivation to become a Buddhist monk was to be a bridge between ancient wisdom of Buddhism and the life of the modern people. One of Shoukei’s recent initiatives is in the corporate world. If there is a corporate in-house doctor, then why not a corporate in-house Buddhist monk? Shoukei and his colleagues engage in on-line one-to-one conversations with employees of client companies.

Shoukei thinks the value of a corporate in-house monk is being a “perfect stranger.” In other words, somebody that has absolutely no conflict of interests, and at the same time, someone that can be trusted. Usually, strangers are not to be trusted, but because this stranger is a monk, the conversation tends to be very spontaneous but also open, not just about issues regarding the workplace, but also personal relationships.

For those listeners who are unfamiliar with Buddhism, I asked Shoukei for a very short description. Shoukei observes that city dwellers in the modern culture tend to live in dualistic world…right or left, good or bad. Buddhism is about overcoming this dualistic view. Through Buddhism, Shoukei believes that we have lots to learn regarding our perspectives.

Conversation uses languages to communicate with one another. However, Shoukei thinks that languages tend to separate, since it is about labeling things that exist in our lives. Therefore, language is a bless, but can also be a curse.

Buddhism is not just about the thought, but also the physical practice. For instance, monasteries like Enkaku-ji in Kamakura, monks practice Zen meditation but that is not the only way of practice. Eating, gardening, cleaning, every single part of life can be Zen or practicing Buddhism. In a sense, it is about destroying the reliance of language, and overcoming the borders of a dualistic world.

However, Shoukei does not deny the dualistic world. There are many benefits from the digital world. But he believes that if we can break the borders of digital world of 0 or 1, the dualistic world, creativity and imagination can take us far beyond.

I found this perspective of particular interest because we need imagination to see things that we cannot see outright. We humans are blessed with imagination, which allows us to escape our present being, and our minds can be anytime, anywhere. Imagination is limitless in a limited world.

There are different types of Buddhism in Japan, notes Shoukei. Kamakura is famous for its Zen Buddhism, whereas he belongs to Jodo-Shinshu or “Pure-Land” Buddhism, which emphasizes surrendering your intentions to the other power, “Ta-Riki.” From this perspective, Shoukei wonders where our imagination come from. Are you the person that is imagining things. Or is imagination itself is something that comes to you.

Shoukei notes that the world-renowned author Haruki Murakami have said that the story itself urges him to write it down. He is not the person that creates the story, but rather the story visits him to express it.

Many monks are heirs of family businesses, but Shoukei did not come from such a background. So, what sparked Shoukei’s imagination to become Buddhist monk, I wondered.

Shoukei replied that as a university student, he initially considered entering the academic or corporate world, perhaps at an advertising agency. But for some reason, he felt that his soul was not willing to take that option. He was intrigued to find more meaningful work, which would be associated with people from the past.

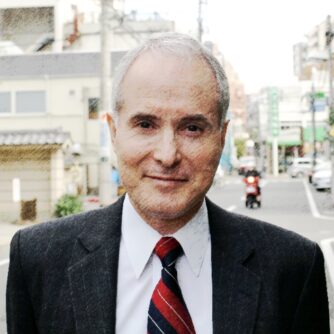

Last year, Shoukei had the opportunity to translate the book, “The Good Ancestor,” authored by Roman Krznaric. Shoukei pondered how he could succeed the effort of our ancestors, taking it to the future people. Transforming the traditional culture of Buddhism that is more relevant to modern people was something that he wanted to pursue.

Shoukei is a contemporary Buddhist monk, and not a translator. Yet, he met Roman when they participated as panelists on an on-line conference, convened by the House of Beautiful Business, a foundation in based in Portugal. He was the only Japanese, and the only Buddhist monk, attending this western conference. His session was titled “The Good Ancestor.”

Roman gave Shoukei a PDF manuscript of his book, and Shoukei was immediately inspired by the content and became a big fan. He proposed to Roman to publish his book in Japanese. The project started, and Shoukei learned firsthand that translation work is very tough.

However, as a Buddhist monk, it was natural for him to think about our ancestors, and to project ourselves as future ancestors came easy. Therefore, he felt that translating “The Good Ancestor” for the Japanese community as a Buddhist monk would be very meaningful.

Before reading the book, Shoukei thought that the role of traditional Buddhist monk is giving ceremony for ancestors, looking back to the past, through rituals or ceremonies. But thanks to this book, Shoukei had an inspiration that giving respect to previous generations is not just looking back into the past, but also for the future generations as well.

I found this portion of our conversation with particular interest since religious leaders are translators of the religion to the worshippers. Also, contemporary Buddhism requires translation from the traditional. Shoukei agreed that the role of any religious leaders is becoming a translator in different contexts, ancient or modern, languages and culture.

I also feel that “digital” is all about transmission, and efficiency. But if the sender and the receiver are in different contextual environment, the data may be exchanged, but the true meaning may be missing. You need translation to convey the meaning.

Shoukei agrees that translation is especially needed in the digital world. Religious leaders bridge the gap or become catalysts between different worlds.

Shoukei notes that in conversations, if one says “A,” the other who receives the message may reply “B”, and therefore the content of conversation may change to “C.” Every time a message is relayed, there is a little bit of change. Something that did not exist before, now comes into existence.

If transmission is 100%, then the conversation doesn’t weave and stays within its original boundaries, and therefore, no new creation. Translation, which allow weaving, the contents become larger than what it started out with.

Shoukei notes that “The Good Ancestor” cautions against speculative capitalism and ever-growing economy. As founder of Commons Asset Management, I have been thinking about long-term, cross-generational investing since inception in 2008. In a sense, we have been trying to be good ancestors. However, disappointment in capitalism is currently widespread. There are severe issues like global warming, social disparity, disengaged young generations that capitalism had left behind, for the sake of growth.

I asked Shoukei a question that I have been pondering about for a while. Why do we need growth. All living organisms grow in the natural world. The same for the economic world, but if it keeps on growing, it is obvious that the planet will be under strain. What is capitalism. What is growth.

Shoukei has been thinking about this topic as well. How we can live better in the world of capitalism. In June, after attending the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos at a very interesting moment in human history, Shoukei stopped by Roman’s house in the UK, where he stayed one night with Roman’s family.

His partner is Kate Raworth, creator of the concept of the “doughnut economics” of social and planetary boundaries, and therefore Shoukei had the privilege of receiving a direct lecture from her. From this conversation, Shoukei sees “capital” as something that is to be used for some other purpose. Thus, capital by itself does not have value. Capital has value only when it is used for other purpose.

He believes the problem of capitalism is the constant urge to attain purpose in the future, whereas Buddhism emphasizes the “here and now.” Shoukei believes we already have enough without sacrificing “here and now” for future purposes. Lets’ start appreciating what we have now, he says.

One of the basic values in Buddhism is this concept of “here and now,” whereas capitalism is destined to project appreciation of “here and now” into the future. Like a horse with a carrot dangling in front, capitalism is a goal-oriented mindset. But Shoukei reminds as that capitalism is not the objectives but means.

Thinking about growth as well as the “here and now,” I posed a question to Shoukei. We see the growth from past, but what will happen in the future if there is no growth,

He replies, it just ages. We grow till the end of life, and then we die. However, the world will keep aging towards the future with destruction and regeneration, death and rebirth that continues to repeat.

Iit does makes biological sense since new generations always adapt to the new environment. The environment always changes on a grand scale, and that is probably the reason why organisms look for growth in the new environment. But it doesn’t grow forever, and the present generation passes the baton to the next.

I believe global health of access to everyone for medical care is a basic human need. But what happens if the human population keeps growing while earth’s capacity is finite. We want to save all the underprivileged people living in poverty, but if everybody prospers, then what happens to our planet. I don’t have an answer for this big question.

Shoukei suggests that when we think about future of our society, there are some lessons that can be learned from Japanese Buddhism philosophy of “Daijo Bukkyo” or Mahayana Buddhism. This is the concept of inter-being, where everybody is interconnected, and nobody can be independent. Everybody is interdependent, not just among human society, but everything.

For instance, the air that we breath cannot be separated from the person. He may be just breathing air, but without air, he cannot live.

Shoukei has a suggestion. If we really want to be sustainable, we need to remind ourselves that we are just animal beings. In other words, we are not the ruler of this planet, but just a part of the planet,

In that sense, the concept of “Anthropocene,” where human influences impact everything on the planet, misleads us unconsciously to believe that we are rulers of planet and evaluate our power and ability far beyond the reality.

Shoukei points out that top scientists agree that we still don’t know anything about the nature of this world. Even in a scoop of soil, we don’t know the exact mechanism of the soil and bacteria. Shoukei urges that we should learn from Japanese Buddhism the fact we are part of that unknown world. We have so many things to learn. We are not the ruler of the world. We do not have the power to control everything in nature.

I asked Shoukei, how do we link the “here and now,” and the quest for knowledge. Shoukei replied that the appreciation of the “here and now” doesn’t necessarily mean self-sufficiency at the current state. We should admit that we are very much ignorant, but our curiosity must grow.

My take from Shoukei’s answer was that there are boundaries for physical growth, but for curiosity growth, mental and spiritual growth, these are free to grow.

Shoukei agrees that there needs to be outlets for growth, otherwise it will be a very boring society or life. Perhaps we are not appreciating and not knowing enough about the “here and now.” We are always in a hurry to see the next growth next stage. Yet, Shoukei believes that appreciating the “here and now” stimulates our sense of wonder.

There was something I was curious about, so I asked Shoukei for his thoughts. There are lots of podcast content out there about mindfulness, and Zen Buddhism and meditation is a topic of discussion. Many of these folks that are talking about mindfulness are entrepreneur types that that thrived on growth. Why is there this global trend toward mindfulness in a world that has been so hyper growth oriented.

Shoukei thinks that mindfulness is very useful, for anybody. Whether those who pursue infinite growth, school children, or patients in a hospital, whoever you are, you can benefit from mindfulness.

A prominent figure in Japanese Buddhism in the 20th century, Daisetz Suzuki, introduced Zen Buddhism to the world, but he recognized himself as practitioner of “Nembutsu” Buddhism, or Pure Land (“Tariki”Buddhism). He introduced Zen to make yourself more mindful, individually, by practice.

On the other hand, “Tariki” Buddhism shows us how live together in a society in more mindful way. In other words, Zen Buddhism had a role to play showing people how they can live more mindful individually, but now, Shoukei believes the time has come to look for ways to achieve collective mindfulness.

I found this a difficult, yet interesting concept. We exist as individuals. But we don’t live as individuals, but as a part of a collective. Shoukei reminded me that in Buddhism, all are interdependent, and there are no individuals. The individual is elusive.

In closing a very interesting conversation, I asked Shoukei for his last words. How do we become “good” ancestors.

After translating the book into Japanese, and several conversations with Roman around this question, Shoukei says that they have agreed to slightly modified the question.

How can we be “better” ancestors

Shoukei notes that if he says “good,” immediately the listener will imagine “bad.” Therefore, if there is good ancestor, there must be a bad ancestor. This sort of dualistic sense of the world.

But in Shoukei’s observations during “houji” or ancestor worship ceremony, nobody gives disrespect to their ancestors. We just give respect. This because we know that our ancestors must have hoped for our happiness. So, the important thing before thinking about the future generation, we need to appreciate the “here and now,” the blessings from the previous generation.

We are the future generation of the previous generation. As future generation of the past, living right know, let us appreciate the gifts from the previous generation.

Let’s enjoy this life, urges Shoukei. That should be starting point to be “better” ancestors.

And, in appreciation of the “here and now,” let’s think how we can pass those gifts from previous generation to the future generation. Living on this planet, yes, we should control our desires. But at the same time, this does not mean sacrificing everything in our current lives.

We cannot decide the future of the society. People who decide their destiny should be the future generation themselves. Therefore, we should not be so decisive. What we can do is to leave options for future generation, says Shoukei.

The spirit of the generation is not just current generation, but past with the future generation. We are not a standalone.