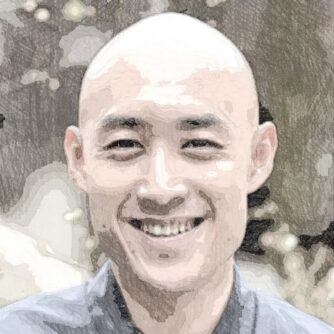

Chris is in a class of her own. She is a professor in Japan, an American of Armenian and Swedish descent, and never had interest in Japan while growing up. When Chris was entering university in 1978, China which was starting to open up, seemed really cool.

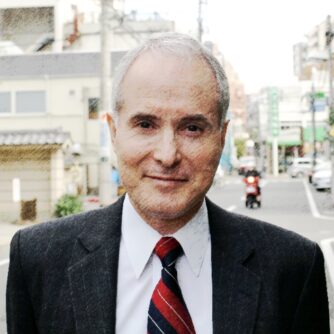

Upon entering Harvard University and meeting the program director of East Asian Studies, Professor Ezra Vogel, changed her life. Professor Vogel who had been a scholar of China, published a book called “Japan as Number One,” urged his students to see the Japanese miracle.

The US job market in 1981 was horrible, so she went to Japan to teach English in Osaka. Because she happened to live next door to the company dormitory for Mitsubishi Electric Kyoto Works, Chris met some people there and got introduced to a job opening for a secretary, so-called OL or “office lady.”

She was handed a uniform, and got really good at serving tea and coffee, which amused Japanese visitors to the company. In one instance, she was serving lunch to visitors from the US, and her boss said to them, “This is Christina. We just hired her. She just graduated from Harvard.” Needless to say, the visitors started to laugh uncontrollably.

Chris’s duties were not just limited to serving tea, but she also did translations and factory tours. Chris loved hanging out in the factories, but clearly, her calling was not to be an office lady in Japan.

She did not know what to do, so decided to back to the US for an MBA and headed for the Stanford Graduate School of Business. At Stanford however, Chris still didn’t know what she wanted to do, so she interviewed with consulting firms and investment banks, and got offers in both. By 1987, the Japanese Bubble was in high gear, and firms were eager hire anybody who wanted to work in or with Japan.

Bain & Company hired Chris for their San Francisco office. Then Chris realized that she was a terrible consultant. She didn’t have the business polish that was necessary to be a good consultant.

But at Bain, Chris realized how much she loved researching businesses. She thought, “This sounds like something that I could do,” and applied for the PhD program at the University of California at Berkeley. She studied corporate groups like Mitsubishi, Mitsui and was hooked. At age 28, Chris finally figured out, “This is what I am going to do with my life.”

She got a job at Columbia University, riding the crest of the Japanese bubble, but when she arrived there, people were beginning to realize that the bubble had burst in Japan. She was riding the elevator at Columbia business school with a professor of economics, and he asked, “Now that Japan is irrelevant, what are you going to do research on?”

But Chris was studying Japanese business groups and cross shareholding, interlocking board of directors, and just around that time Columbia Law School was getting deep into corporate governance research. Chris was suddenly relevant again.

Chris, then got an Abe Fellowship to study corporate governance in Japan, allegedly for one year in 2000. She is still here.

While Chris was a visiting scholar at University of Tokyo, an article caught her eyes. An English language business school at Hitotsubashi University was being established, and she thought, “Maybe this is for me.” She joined the English language business school at Hitotsubashi (ICS-Graduate School of International Corporate Strategy) in 2001.

For someone who had no idea what she wanted to do, somehow everything was starting to make sense. The dots were starting to connect.

In 2009, Chris was nominated as a board member for Eisai Co., Ltd. a pharmaceutical company, with strengths in neurology and oncology. The company is a public company, but the CEO, Mr. Haruo Naito is the third generation “owner.” The family members are not controlling shareholders, but Mr. Naito has strong influence and direction of the company.

Probably because of his absolute standing inside the company, Mr. Naito has been a champion for corporate governance. Eisai has a long tradition of having more external independent directors than internal. They have also adopted US style board with audit, nomination and compensation committees. The chairman of the board is also external, unusual for Japanese companies.

The story goes that at the annual shareholder meeting in a previous year, even though Eisai’s corporate motto was “human health care,” written in Florence Nightingale’s handwriting, a shareholder asked, “Why aren’t there any women on the board?” It is said that the chairman of the nomination committee, Professor Ikujiro Nonaka of Hitotsubashi University promised that next year, there would be a woman board of directors. Hence, Chris was nominated.

Chris remembers being terrified as she was entering her first board meeting. The doors opened, and she was in the boardroom filled with black heads of all Japanese men. But she also remembers how everybody was very polite, even though she was the youngest person on the board.

Learning the basics of the practice of corporate governance, in 2012, Chris was nominated as the external independent board director of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries. Where Eisai was forward looking, global, and nimble, MHI was very old, very traditional, their businesses being defense, power plants, and shipbuilding. Chris said “no” to the executive recruiter many times when approached for that position.

Finally, she agreed to lecture the board of MHI, and basically told them how behind the times the corporate governance at the company was. Yet she admired their sincerity for reform, and finally decided to take their offer.

At the very first board meeting at MHI, the men were even older. During her introduction to the board, she said that she was really scared. The top executive replied, “Well, we are all really scared too.”

But scared or not, Chris was determined to do the job. She knew what an independent director should do, based on her experience at Eisai. A good corporate director asks many questions, looks for things overlooked, interrogates why things happened, what information was the decision based on, and on occasion, why inconsequential matters must be determined at board meetings. “Being straight and direct” is Chris’s motto as an independent corporate director.

At Hitotsubashi University, Chris is the director of the Shibusawa Scholar Program. The Ministry of Education funded the launch of this “global leadership” program, but Chris and her faculty colleagues at Hitotsubashi felt the term was a bit of a cliché and wanted to call it something else.

Eiichi Shibusawa, the father of Japanese capitalism, is held dear to many affiliated with Hitotsubashi. Eiichi had helped to rescue the predecessor of Hitotsubashi University from the verge of collapse in the early years and was a supporter and benefactor of the university.

His purpose for founding companies was not about maximizing profits, but rather for the benefit of the society. Eiichi Shibusawa was Japan’s first social entrepreneur in the modern era. He was also global.

When Eiichi was 27 years old, he was part of the shogunate delegation to the Paris Exposition in 1867. He left Japan as a “samurai,” but the industrial society of the West completely opened his eyes, and Eiichi returned with visons for establishing new businesses that will bring prosperity to the nation.

Hence, Chris and other faculty members felt that Eiichi Shibusawa was an ideal role of model. The program strives to open the eyes of young people who can become Eiichi Shibusawas of the 21st century.

When students join the program during their second year, most of them don’t really know what they want to do, often being disconnected with society. But when they return from their study abroad program, in Chris’s eyes, their change in attitude is “amazing.”

“Out of Your Comfort Zone” is the motto for the program.

In general, Chris feels that Japanese youth “is great.” The “raw material” is very thoughtful and well educated, perhaps not so good with debate or speaking up with things, but well trained in math and Japanese language skills. However, Chris expresses her concern that their English education “is horrible,” and that Japanese young people are “mis-educated.”

After 8 years with the Shibusawa Scholar Program, Chris feels that the entering class is getting better every year. However, the education system is still calibrated to produce the perfect company “salary-man” of the Showa Era (The era of “Japan as Number One” in the latter part of 1925~1987 period).

Cramming in brilliant young people in lecture halls of 500 “is a waste.” The useless hierarchy at school clubs is so horrible to watch, “it makes me crazy” says Chris.

So, what do people outside Japan misunderstand about Japan? Chris feels gender issues are very complicated, but people outside of Japan often have a one-dimensional view. People often say to her, “Isn’t it difficult being woman professor and board director in Japan? You must be discriminated against.”

In fact, Chris feels that every day she receives much kindness and respect, and Japan is a much better place to be a woman these days than any time in the past. Admittedly, foreign women have some advantages, being outside of Japanese society. There are “still many serious challenges”, but Chris observes that Japan is taking gender problems more and more seriously.

So, what to people in Japan misunderstand about themselves? Japanese think they are a country with no diversity, and so homogenous, but history and geography show that that this is just not true, notes Chris. Japan stretches from north to south, and the climate, geography, food, products, lifestyles of the archipelago are very diverse. When you travel Japan, you will encounter various dialects and customs, even in these modern times.

The black headed salary-man may all wear the same suit, but everyone’s personalities are really different. Chris believes that Japan needs to value and prize its natural diversity.

Kimono is a passion for Chris. She has always loved everything to do with textiles. Crafted from silk, cotton, or linen, the kimono is the ultimate textile. The weaving styles, the dyeing styles are like nothing else in the world, marvels Chris.

Chris believes that the kimono is the ultimate sustainable clothing product. Made from silk from worms that feed on mulberry, the kimono also uses natural vegetable dyes, kimonos “are from the earth.”

Kimonos are kept forever, passed down the generations. It is not like fast fashion. And when it is finally worn out, the fabrics can be used for cushions or wallets. This special Japanese sensibility that surrounds the kimono, is the appeal for Chris.

In theory, kimonos can be appropriately worn for all occasions, for shopping, dinner, and company related events. However, it does take a long time to put on a kimono. 20-30 minutes is considered fast, and it takes Chris over an hour on a good day.

When Chris is not in a kimono, she wears UNIQLO. We are used to throwing on our clothes in the modern era. But with the kimono one has to be careful and deliberate. There are so many things to consider. Who you are going to be with? What is the event? What is the season? How do I want to look?

This is what Chris likes about the old Japan: the sense of manners. Sometimes it feels a bit superficial, but it is also nice to pay that much attention to detail. Chris feels that purposeful with your actions is like a kind of mindfulness.

So much in the Japanese culture is so purposeful, observes Chris. One is always considering how to place oneself in relationship with the world and the seasons and surrounding people and objects. As a non-Japanese it is fun to immerse into the Japanese culture, an experience out of the comfort zone for Chris.

Chris also has found that wearing kimonos is a great way to bond with senior Japanese executives. After the board meetings where she has what she has to say and a role to play as an independent corporate director, she shows up later at the company function wearing a perfectly worn kimono for that occasion. Chris receives lots of happy and surprised reactions. “It gives me credibility.”

Last word on the “ojisan.” “Ojiisan” (two “i”s) is your grandfather. But “Ojisan” is like your uncle. And, “there are some annoying uncles,” says Chris. You can look to the older men in the organization or society as your enemies, or you can choose to look at them as uncles. Annoying at times, old fashioned, perhaps, but sometimes “kind of cute,” according to Chris.

The “ojisan” can sometimes forget that he is living in the 21st century. And when there are only men speaking at a conference, Chris has to blurt out “C’mon ojisan, get a grip.”

But she also feels that not criticizing the essence of these people is important. These senior Japanese men are known for saying some questionable and harmful things and should be criticized for it. But they have built an amazing country and have done impressive things, says Chris.

So, Chris’s message to the ojisans of Japan. “Jump out of your comfort zone!” And one great way is to engage with the younger people, like the Shibusawa Scholars. Chris closes the conversation by noting that the generation gap in Japan may be a bigger issue than the gender or diversity gap.